(Last updated 3 January, 2025)

Richard (Dicky) Barrett

Although Dicky Barrett’s place of birth has been regarded as uncertain, Anne Hodgson’s and Ron McLean’s research indicates there are records in the United Kingdom stating that Dicky was born in Cherry Garden Street, Rotherhithe / Bermondsey, South East London in 1807 to parents Matthew & Sarah Barrett. Dicky was their third child, one of seven children.

Born and raised in London in the Northern Hemisphere, Dicky lived 18,500 kilometres away from Wakaiwa’s Nga Motu, Taranaki in the South Pacific. Dicky’s London was the centre of world trade and was a magnet for migrants from not only within Britain and Europe, but from around the world and particularly from Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Britain led the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. With a diverse population of around 1.5 million, London was not only one of the world’s biggest cities, but it was also the most dynamic, emerging from a period of economic downturn after the Napoleonic Wars.

According to McLean, ‘…the South Bank [had became] a dumping ground for the dirtier trades that had been shut out of the City. Tanners and leather dressers were confined to Bermondsey because of the obnoxious nature of their trade, and by the end of the eighteenth century, Bermondsey was characterised as a place of slums and alleys’.

Despite his impoverished upbringing, Barrett did learn to read and write, as is evidenced from the journal that he went on to keep, and in other correspondence such as letters to his family. It is possible that young Dicky attended St. Mary’s Free School in Rotherhithe.

The local docks were Dicky’s second home. From an early age Dicky would have been captivated by the stories told by sailors who frequented the local taverns. Their tales of far-off lands and daring adventures would have fired up his imagination, filling his young mind with dreams of being a sailor / trader. Retired sailors would have coached young Dicky in the art of navigation, how to tie knots and the secrets of the sea.

Some of Dicky’s neighbours may have been former convicts who, after having served their sentences in the penal colonies of Australia, returned home to England.

There is a record of Richard Barrett, aged 14, being indentured in the British Merchant Navy, bound on 12 January 1821 for five years. This would link with the age of Dicky Barrett as he too was born in 1807.

What motivated the young Dicky Barrett to go to sea? Dicky was aged nine when his mother died. He may have been unhappy at his father’s re-marrying. Or he may have simply needed to get out and earn a living, which in those days would have been common for children at age 12 to 14 or younger. As Dicky’s grandfather was a ’waterman’; and his father was a ‘mariner’ and ‘lighterman’, it made sense for Dicky to seek a trade in the maritime industry.

While the British nation was the victor, and the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 brought peace, the economy struggled while adjusting to a peace-time economy. Moreover, a succession of bad harvests resulted in famine for many.

The more temperate climate of the South Pacific and the economic opportunities to be found in the new world would also have beckoned to young Dicky.

After gaining qualifications and experience during his time in the merchant navy, on 12 January 1826 Dicky Barrett set sail as a crew member on board a trading vessel bound for the South Pacific. As we shall see, young Barrett was an adventurous, inquisitive and gregarious man, bound for a very interesting life.

By 1828, Dicky had become the first mate, with John (Jacky) Love as the captain, on the 60 ton schooner Adventure. The vessel was owned by Sydney merchants Thomas Street and Thomas Hyndes. The Adventure was built in 1827 at Hyndes’ timber yard in Cockle Bay, Sydney. It was a two-masted schooner, 40’8″ long, 12’3″ wide and 5’9″ deep (Caughey, 1998:264)

Jacky, Dicky and their crew worked the trans-Tasman trade, leaving Sydney in February 1828 loaded with clothes and blankets, muskets and powder, tobacco, razors and rum, barley and corn, and discharging to storehouses in Kororareka (Russell) and in what is now known as Queen Charlotte Sound and Port Nicholson (Wellington). They returned to Sydney with pigs, flax and potatoes.

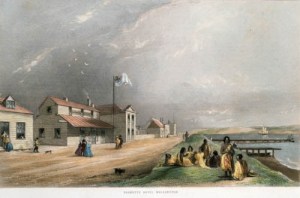

Arrival at Ngā Motu, 1828

On its second trip in 1828, the Adventure was intercepted off the coast of Taranaki by two waka (canoes) paddled by 40 warriors from the Te Atiawa tribe, led by rangatira (chiefs) Honiana Te Puni-kokopu (Te Puni) and Te Wharepouri. On board the Adventure along with Love and Barrett were George Ashdown, James Bosworth, William Bundy, Joseph Davis, William Keenan, a chap called Lee from the USA, a chap called Oliver, James Robinson and Daniel Sheridan and Robert Sinclair.

The Adventure’s arrival off the coast of Taranaki came almost 60 years after Captain James Cook’s first voyage in 1769. Although Cook returned to New Zealand twice, he did not go ashore in Taranaki.

Up to that point Te Ātiawa had limited exposure to Europeans. However, the iwi would have acquired some knowledge about the benefits of contact with Pākehā (European) – particularly from the acquisition of iron tools, woollen blankets and muskets – from the experiences of other iwi and from some limited previous contact, and were keen to build a trading relationship with Pākehā for the purposes of securing arms and other goods. While Pākehā had set up trading stations in other parts of Aotearoa, the lack of a natural harbour in Taranaki meant traders lacked the incentive to go ashore and investigate the potential for trade on their own initiative, let alone establish a permanent base there.

Love and Barrett, keen to expand their trade connections, agreed to go ashore at Ngā Motu (The Islands) to see what was available to trade, where they inspected flax and pigs. According to Bremner, ‘Te Atiawa, pressing for a trading post permanently occupied by Pakeha to ensure prosperity and preservation, presented high born Te Atiawa women to Barrett and Love. Barrett partnered Wakaiwa and he took the Māori name of Tiki Parete. Jacky Love’s Māori name was Hikirau and his partner was Mereruru Te Hikinua. By staying at Ngamotu (as the site is called now), Barrett, Love and their men became the fist European residents in the Taranaki region’.

The practice of giving a wife to distinguished visitors was a well-established custom within Polynesia as the people regularly travelled from their home lands to other islands. The relationships formed were accompanied with land transfers which in turn became inheritable by the offspring of visitors (History and Traditions of the Māoris of the West Coast, North Island of New Zealand prior to 1840: Chapter V – The canoes of “The Fleet“).

Some 130 traders had established trading posts between 1827 and 1840 making Love and Barrett one of the first, helping to generate the flax trade boom from 1829 – 1832 (Bentley, 2007). Around that time there were an estimated 300 Pākehā living in Aotearoa/New Zealand, and at least 100,000 Māori (Te Ara: Maori-Pakeha Relations).

Barrett and Love went on to monopolise the Taranaki flax trade.

“Flax was planted up to 30 miles up the coast by neighbouring tribes who gave the two pakeha first right of purchase. Coastal traders complained that they could not acquire cargoes in Taranaki”.

Bentley, p153

Wakaiwa Rāwinia

In complete contrast to the slums of East London, Wakaiwa’s rohe was a place teeming with natural beauty. With a backdrop of the majestic Taranaki Mauna, surrounded by lush bush, fresh rivers and streams flowing down to the coastal plains of flax, ferns and native grasses boarded by black sand beaches, and a population of around a mere 2,000, the land was pristine and unpolluted.

As with all her people, Wakaiwa possessed a deep connection to her ancestral lands and lived within several closely related and inter-connected hapū. Living within her tikanga (culture) Wakaiwa learned the values of manaakitanga (hospitality, protection, kindness, and respect for others) and whanaungatanga (kinship and close connection between people). She was taught the ancient customs such as weaving intricate patterns into flax mats and the role and significance of performing haka and waita.

Successive generations of Honeyfield descendants were told by their parents that Wakaiwa was a ‘Māori princess’ by dint of her being the granddaughter of a senior chief (Ariki). While there was no equivalent concept of a European princess in traditional Māori society, Puhi came very close. Puhi are daughters of rangatira, were of high rank and highly respected. They were renowned for their beauty, their courage, and their leadership. Marriage for such highly ranked women were arranged in the interests of the iwi /hapū. The duties of such women cantered on hospitality and generosity to visitors. All those attributes were attributed to Wakaiwa.

Wakaiwa’s first contact with Europeans probably pre-dated the arrival of the Adventure in 1828 as trans-Tasman whaling and trading was established before that time. However, those interactions would have been for short periods of time as traders purchased flax from Māori to make ropes for shipping in exchange for European goods.

Wakaiwa Rāwinia (also known as Rangi, but Barrett called her Lavinia, an anglicised version of Rāwinia) was the daughter of Eruera Te Puki-Ki-Mahurangi and Kuramai-Te-Ra and granddaughter of Tautara, the ariki (paramount chief) of Te Atiawa, and Maheuheu. Tautara, who resided at the Puketapu Pā (in the present day Bell Block), was the son of Te Puhi-Mañawa and Mairangi. Tautara was related to ariki in other iwi and could trace his whakapapa (genealogy) back over six hundred years, to the origins of Maori from the southern Cook Islands and Tahiti in East Polynesia. Angela Caughey traced Rāwinia’s ancestry back seven generations to Tukiarangi. Rāwinia’s full whakapapa is available here.

Being a woman of such high-ranking, Rāwinia’s marriage to Barrett was a reflection of the high status in which the trader was held by Te Atiawa.

Te Atiawa trace their origins to their founder Awanuiarangi, and their ancestral migration to Aotearoa on the Tokomaru waka (canoe) in about 1350.

According to research by Angela Caughey and others Rāwinia belonged to the Ngāti Rāhiri and Ngāti Maru hapū of Te Atiawa (J & H Mitchell, p333). There are many references to Rāwinia being of the Ngāti Te Whiti, such as evidenced by Rāwinia, her children and her father being recorded as Ngāti Te Whiti in the census completed by Donald McLean in 1847.

Rāwinia’s grandfather, Tautara has been described variously as belonging to the Puketapu, Ngāti Rahiri and Ngāti Tawhirikura hapū of Te Ātiawa. I have yet to find any evidence of a link to the Ngāti Maru.

In any case, Rāwinia can be unambiguously described as part of the collection of hapū that were resident at Ngā Motu. See my posting on Rāwinia’s hapū connections for more details and analysis.

By the weight of evidence the Mitchels rightly concluded that, ‘By virtue of her own status within the tribes she afforded protection and support that helped ensure the success of her husband’s commercial endeavours’ (page 335). The Mitchells included Rāwinia in the section of their publication covering Nga Wahine Toa – brave women or women leaders.

Rāwinia was reputed to have been one of the most beautiful and talented Māori woman of her time.

Barrett family

Dicky and Rāwinia had three daughters. Caroline (Kararaina) was born at Nga Motu in February 1829, followed by Mary Ann (Mereana) in December 1831. Sarah (Hera) was born in June 1835 at Te Awaiti Bay on Arapawa Island in Tõtaranui (Queen Charlotte Sound).

Mary died in 1840 at the age of eight years. Sarah married William Henry Honeyfield on 5 April, 1853. Caroline married James Charles Honeyfield in 1865.

Departure from Ngā Motu

As well as being a trader, Dicky went on to become an explorer, a whaler, interpreter and agent to the NZ Company, a publican and farmer.

After leaving Taranaki in 1832 (covered in a separate posting) Dicky established a shore based whaling station in Te Awaiti Bay, Tōtaranui (Queen Charlotte Sound).

Not long after the New Zealand Company’s Tory arrived in 1839, Dicky was engaged by Colonel William Wakefield acting as interpreter in negotiations for the sale of land at Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Port Nicholson, Wellington), Tōtaranui and Taranaki. More details about the negotiations and subsequent disputes are covered here.

Wakefield apparently described Barrett as being fond of relating “wild adventures and hairbreadth scapes”. Edward Jerningham Wakefield (William’s nephew) described Barrett at the time they met as:

Dressed in a white jacket, blue dungaree trousers and round straw hat, he seemed perfectly round all over, and good-humoured smile could not fail to excite pleasure in all beholders.

Adventure in New Zealand

Ernst Diefenbach, naturalist on the Tory, noted Barrett’s sunny disposition.

‘His ruddy and good-humoured countenance showed, at all events, that such a life had not occasioned him many sleepless nights, and that in New Zealand a man might thrive, at least as far as regards his bodily welfare’.

J & H Mitchell, page 336

The only known portrait of Barrett (below) is undated but was possibly done following his whaling injury in 1845 when he was forced to stop working. By that time Barrett had lost a lot of the weight that Wakefield wrote so humorously about him in 1839.

Wakefield named a hazardous reef at the western side of the entrance to Wellington Harbour, Barrett Reef, after Dicky.

There are testimonies to Barrett’s skill for storytelling. McLean stated that:

[Barrett] regaled credulous settlers on numerous occasions with tales about the siege at Otaka Pa, including long and detailed accounts of cannibalism to shocked audiences. Other accounts included tales of being tied to a stake while Māori prepared to cook him for dinner (page 74).

Dicky went on to develop various business interests in the new settlement in Wellington, including establishing Barrett’s Hotel which became something of a civic centre in the new colony.

Jerningham Wakefield wrote the folloing description of life at Barrett’s hotel.

The house was always half full of hungry natives and idle white men who had wondered from the whaling stations, and large iron pots and spacious table constantly extended his too undistinguishing hospitality to all applicants. He was quite proud of the change which he had aided to produce in the appearance of the place and the prospects of his friends the natives, and used to spend his time in watching the proceedings of the newcomers; sometimes mystifying a whole audience of gaping immigrants by a high-flown relation of a whaling adventure, or some part of his Maori campaigns.

Bentley, p220

Return to Ngāmotu

Barrett’s whaling business suffered heavy losses and, after he was forced to lease his hotel in 1841, he led a party of Te Atiawa back to Taranaki and went on to help establish new settlers in New Plymouth.

While in Wellington however, Barrett, as the New Zealand Company’s chief agent for the proposed settlement of New Plymouth, was engaged by the Plymouth Company’s surveyor, Frederick Carrington, in January 1841, as a pilot / interpreter on Carrington’s mission to select possible sites for the establishment of a new settlement. As Barrett was already planning on returning to Ngāmotu he set out to persuade Carrington to select Ngāmotu area as the new site. One of Barrett’s tactics was to guide Carrington around the steep and mountainous areas of land in Queen Charlotte Sounds, and the Te Atiawa settlement at Motueka, where the land was low, swampy and liable flood from the rising sea. The area then known as Nelson Haven, which on closer inspection had the advantage over Taranaki in having a natural harbour, was over-looked by Barrett.

A small number of Te Atiawa had remained at Ngāmotu, keeping the home fires burning. They lived on one of the islands, Mikotahi, which was a semi-island fortress. Among this group of people were Rāwinia’s parents.

On 28 March, 1841, Dicky and Rāwinia were married by the Wesleyan missionary Reverend Charles Creed at the Mission House. Their surviving daughters Caroline and Sarah were also baptised that day. In his December 1846 letter to Donald McLean (at that time the Inspector of Policy), Harcourt Aubrey wrote:

“His [Barrett’s] marriage gave him additional influence over his wife’s people, for the natives seem now, fully as as well Europeans, to understand the binding nature of the marriage contract”.

Paperspast,National Library

By then Aubrey would have got to know Barrett quite well, having came out to Aotearoa/New Zealand in 1840 as an assistant surveyor with Frederick Carrington. In his letter Aubrey described Barrett as “a remarkable individual”, having experienced much in his 20 years in Aotearoa.

At about the time of Barrett’s return to live in Ngāmotu he wrote a letter to his brother asking for news of home and his family, but also complaining about previous correspondence not being replied to. It was not until 1842 that Barrett had news from his family in England, some 15 years after he had left home (McLean).

Barrett went on to be one of the first men to drive cattle from Wellington to New Plymouth, and he introduced new crops and vegetables to Taranaki. He established a cattle farm and horticulture business, while continuing in whaling and trading in flax.

The pleasures of life at Ngamotu for the Barrett family, and the character of Dicky Barrett, are evident in the following newspaper article:

Mr Barrett resided in a wooden house, and here his two daughters, Caroline and Sarah, sported their childhood. Here they laved [sic] their youthful limbs in the waters of the clear little lake, or flashed their bare brown bodies through the blue waves that rolled around the Sugar Loaves and entered the little reef bound cove into which the whales were towed when killed. They ran over the hills and plucked ripe Kea-Kea, or they stored the flax honey in small bottles as a curious present to some white new chum friend. Then, when tired of their sport, they took their way homeward to have a tune on the organ. I am not joking. As Mr Hursthouse’s piano has been named, it is right that an instrument, which preceded it by many years to the colony, should also be mentioned. Mr Barrett’s was a hand organ: and was in all probability, the first instrument of the kind that ever reached the colony. He had certainly had it for many years when I first saw it in 1842 or 1843. Many a tune have I played on it, tunes unforgotten still, and one at least of them never heard elsewhere.

It must not be thought that Mr Barrett was an ordinary whaler. A very short, powerful, round-faced man was he, good-natured looking but determined – a man to stand no nonsense. The feelings of the best lady in the land would not be shocked by Mr Barrett’s carriage, or by any word or look from him. I have passed more than one evening with him in such society in early youth, and I know this to be a fact. mr Turnbull, in Jacob Faithful to those who have read that work – and who has not? – will saye [sic] all description of Mr Richard Barrett.

Unknown author published in The Press, December 12, 1889

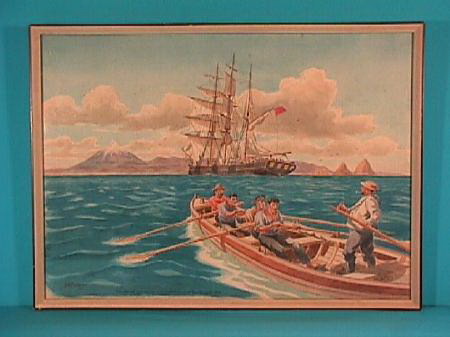

Right from the beginning of NZ Company emigrant arrivals at New Plymouth, Barrett and his crew regularly provided assistance to new emigrant arrivals in New Plymouth, providing them with temporary accommodation and assisting with the landing of cargo with his whaleboats. On the arrival of the first ship, The William Bryan, this was said about Dicky Barrett:

Barrett, an ex-whaler, was a noted character in early Taranaki. He was a powerful, frank sort of fellow, and seems to have been a general cicerone to the first settlers.

Henry Brett

In a letter to the directors of the Plymouth Company on May 2, 1841, Mr George Cutfield wrote that:

Mr Barrett has done everything in his power to assist us in land the cargo [from the William Brian] with one of his whaleboats for which I shall have to pay him.

Wells

The watercolour above was painted by Arthur Messenger and captures one such scene in 1842.

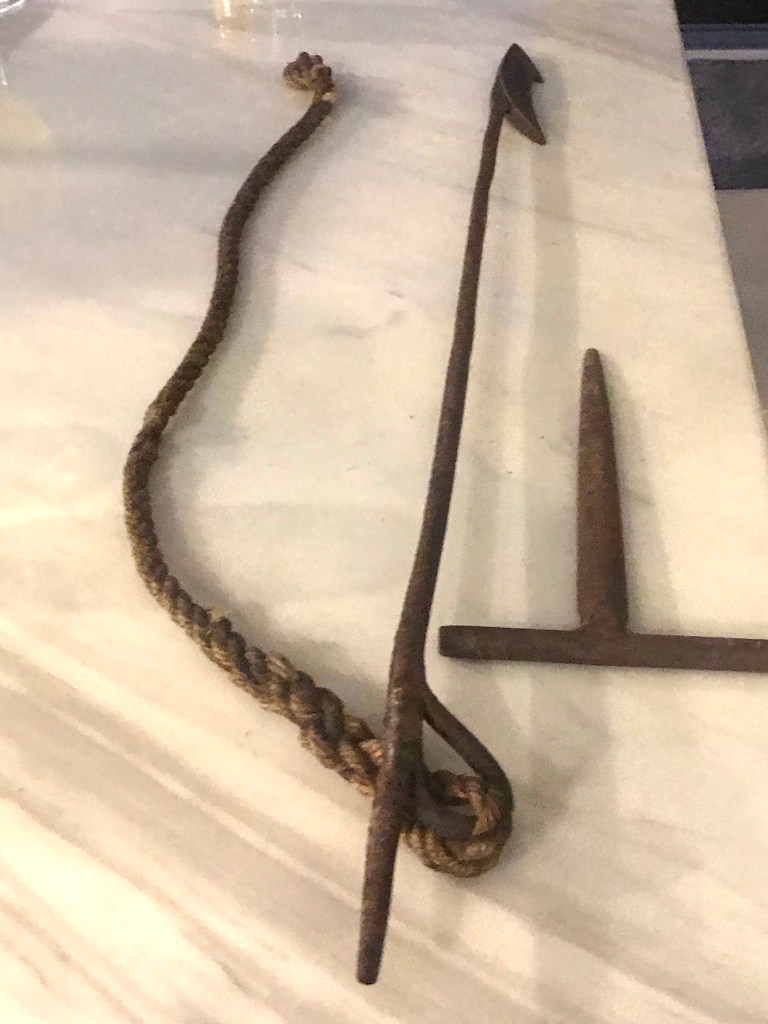

Barrett’s shore-based whaling station, consisting of trypots, harpoons, wind lasses and long boats that lay on Ngāmotu beach, could be quickly utilised whenever spotters on the lookout at nearby Paritutu saw a whale offshore. ‘Once caught the carcass was floated back to shore where it would be stripped of baleen and oil and the remains were left to rot on the sand’. (from Ngamotu – more than just a beach, Puke Ariki Learning & Research).

Whenua

As Barrett was instrumental in securing land at New Plymouth from The New Zealand Company, he was allocated Barretts Reserve A, 23 hectares (56 acres) between the Hongi-hongi Stream and what is now Pioneer Road (which used to be part of Barrett Road).

Another 68 hectares (168 acres) that became known as Barrett Reserves C & D had been given over to Barrett by Rāwinia’s father, Te Puke Mahurangi, when Barrett first partnered Rāwinia in 1828 (in keeping with the well-established Polynesian custom of giving local interests to distinguished visitors). Transfer of the land at the time would have been in accordance with the Māori custom called take tuku (right of gift).

The area contained Kororako Pā. Part of this – 5.67 hectares of what was within Barrett Reserve D – was subsequently gifted by Dicky and Rāwinia’s son, Barrett Honeyfield, to the local authority in the early 1900’s. The land containing the pā was acquired by the New Plymouth District Council in 2012 and is recorded as wāhi tapu (a place regarded as sacred to Māori) in the New Plymouth District Plan. The area is identified as an archaeological site by the New Zealand Archaeological Association, as site 19/52. The defensive ditches of the pā area not easily visible today and an old farm track that led over the pā is now used for pedestrian access (Barrett Domain Management Plan, New Plymouth District Council, August 2013). The photo below taken in January 2019 shows that pā on the left hand side.

The official name of Barrett Lagoon was changed to Rotokare / Barrett Domain under the Treaty of Waitangi Deed of Settlement between the Crown and Te Ātiawa in 2014. The reserve has a number of attractions and walkways. The location of the pā is set out in the map below (source: New Plymouth District Council).

Barrett’s land holdings were confirmed in being awarded 73 hectares (180 acres, being sections 23 and 37) by the Spain Lands Commission in May, 1844. Commissioner Spain also awarded 24,000 hectares to the New Zealand Company and 40 hectares to the Wesleyan missionaries (Dicky Barrett Part 3: Quest for Land, by Rhonda Bartle, Puke Ariki Learning and Research).

In August 1844 Governor Fitzroy, being critical of Commissioner Spain and Barrett’s role in the NZ Company land purchases – particularly in the transactions not having involved or recognised the interests of Te Ātiawa who were absent or held in captivity by the Waikato at the time of the land purchases – set aside the Commissioner’s award of 24,000 hectares to the NZ Company, substituting it for a 1,400 hectare block which included the town site and immediate surrounding area. However, no change was made to Barrett’s land holdings.

In a letter to the then Inspector of Police, Donald McLean in December 1846, Harcourt Aubrey described Barrett’s farm as being the only one of any consequence in the Moturoa area. Aubrey noted:

“…the readiness with which Mr Barrett afforded me information on every required topic, and before we parted he required me to assure you that he should always feel the greatest pleasure in rendering you any assistance that lay in his power”.

Papers Past, National Library.

Fitzroy was replaced as Governor by George Grey in 1845. Grey managed to purchase more land for European settlement in 1847, including blocks at Tataraimaka and Omata.

According to the Taranaki Maori Land Court minute No.7, page 205, Rāwinia was also awarded interests in Ngāti Rāhiri sections 3 and 9 and Rātāpihipihi A East block (H & J Mitchell, 2014, page 347).

Barrett’s role in the new community of New Plymouth diminished somewhat after being criticised by Te Ātiawa and Pākehā alike for his role in what became highly disputed land sale negotiations between the New Zealand Company and Te Ātiawa. Another influence in Barrett’s declining influence would have been the Ngāmotu hapū established their own trading relationships with colonists.

It is worth noting however, that much of the subsequent land disputes that subsequently gave rise to the Taranaki Wars in the 1860’s was due to disputed land transactions between the Crown and Te Atiawa.

Despite such setbacks wihin the community, Barrett’s whaling operations continued. Soon after Governor Fitzroy’s decision some twenty tons of oil and more than one ton of whalebone from Barrett’s whaling operations were shipped to Sydney (Wells).

As the two daughters of Dicky and Rāwinia married Honeyfields, the Barrett land eventually came under Honeyfield ownership.

Dicky Barrett died at Moturoa, on 23 February 1847, possibly from a heart attack or following injury after a whaling accident. He was buried in Wāitapu urupa (cemetery) at the seaside end of Bayly Road, adjacent to Ngāmotu Beach, New Plymouth, along side his daughter Mary Ann. They were joined later on by Rāwinia in 1849 and Hannah, daughter of William and Sarah, in 1861. Wāitapu was the first cemetery in New Plymouth and the first recorded burial was Mary Ann.

More about Barrett’s whaling operations at Moturoa, the injury and his declining health is set out in the Whaling at Moturoa posting.

Barrett’s will left one third of his estate held in trust to pay income to Rāwinia for life. The rest of his estate was left to his children.

According to a letter from the Crown’s Surveyor, Edwin Harris, to the Colonial Secretary dated 9 August 1847 (following the Crown’s purchase of the Grey Block on land in 1847) 120 acres (49 hectares) were reserved especially for ‘Barrett’s widow and children that they should have in exchange for land at Moturoa A block. The Moturoa native reserve included Otaka Pā, the Waitapu urupa as well as 56 acres of the estate claimed by the late Richard Barrett which has been cultivated and is in the possession and occupation of natives’ (Boulton, page 99). Boulton also stated that ‘Barrett and his whaling crew … in exchange for their skills as traders and whalers, had been given use rights to portions of tribal lands’ (page 54).

Indeed, of the crew who were on board the Adventure in 1828 and who went on remain with Barrett – Bosworth, Bundy, Robinson, Sinclair and Wright – all were granted sections of land at ‘Whalers Gate’ in 1847 (Mullon, p 5).

The exchange referred to by Harris appears to have been to formalise the return to the Ngāmotu hapū as native reserve the 56 acres of land that had been allocated to Barrett by the New Zealand Company. The transfer was negotiated by Donald McLean, who noted in his 17th August 1847 letter to the Colonial Secretary, that the Māori reserve “includes 56 acres of the Estate claimed by the late Richard Barrett, which had been cultivated and in the possession and occupation of the natives …. In the absence of an Executor to represent Mr Barrett’s interests, I have proposed to his widow and children that they should have in exchange for the above land at Moturoa, a block of 120 acres beyond and adjoining to Mr Spain’s award and forming, with two other sections within that award, a continuous block, of which a considerable portion was cultivated by Mr Barrett” (Papers Past, National Library).

The background context of the re-occupation of the land after Barrett’s death appears to have been in relation to a long-running dispute between Barrett and some of Rāwinia’s kin. Donald McLean, then in the role of Sub-Protector, Protectorate of Aborigines, noted in October 1844 that Barrett had complained to him that “Wiremu Kawahu and Poharama had fenced off the road upon which he carried his produce, and drove cattle to and fro putting him at considerable inconvenience as he would have to go a round of a mile with his horses and cattle” (Papers Past, National Library). According to McLean, the natives had various grievances leading them to fence off the road, including that Barrett had owed them for some timber that had not been paid. Making it harder for Barrett to earn an income to repay debt does not seen like a sensible intervention. The more likely cause was due to those who refused to accept the sale of land by the Ngāmotu people to the New Zealand Company in 1840, and in particular Barrett’s acquisition of land including the site of the old kainga (village) and associated cultivations. They also apparently had a dispute with “Barrett’s natives [including] the father [Eruera Te Puki-ki-Mahurangi] of the native women he is married to” – probably due to the land dispute. I feel it is worth noting that Eruera stood up to other Ngāmotu rangatira, representing further evidence of his being of rangatira standing.

We can only imagine the grief and stress that Rāwinia and her children must gone through after Barrett’s death, and to then have the land dispute with their kin manifest in occupation by those kin. McLean’s subsequent intervention and assistance to provide land in exchange for that returned to the hapū would no doubt have been welcomed by the Barrett family.

Donald McLean went on to play a substantial role in the colonial government, respected by settlers for his pragmatism, and by Māori for his te reo skills and understanding of their culture, but stained by his controversial role in land sale negotiations. He eventually became Minister of Native Affairs and Defence and a substantial land owner in the Hawkes Bay.

Rawinia’s native reserve lands passed through Native Court determinations to the Honeyfields. In the early 20th century one of the Honeyfield family gave a portion of a block at Ngāmotu as a public reserve (H & J Mitchell, 2014: 347).

Rāwinia died almost two years to the day after Dicky passed away, she was only 38 years of age.

In an acknowledgement of Rāwinia’s contribution to the early history of New Plymouth, Rawinia Street was named after he. Located in the suburb of Moturoa, Rawinia Street is adjacent to the site of Otaka Pā.

More recently, the Puketapu Bell Block Community Board resolved to name a new subdivision road Wakaiwa Drive. The subdivision was developed on land that was previously the Jones whānau farm (Source: Julie Johns).

Port Taranaki named one of their pilot vessels ‘Rawinia’; the first of which was launched in 1961 and the replacement in 2008 (see here for details of the latest one).

Herbert Mullon described Barrett as “one of the outstanding men in pre and early colonial days, respected by Maori and Pakeha (page 25).

Over 75 years after Barrett’s death, his memory and his legacy lived on:

Recalling one of the most widely known and loved men of his day in New Zealand, whether by Maori or Pakeha, Richard (Tiki Parete), whose sterling integrity and hospitality were watch words, who took part in the Ngatiawa – Waikato Native wars, and who through his marriage with the sister of Te Wharepouri, was able to assist greatly the negotiations of the first colonisers; the man, in fact, whose opinion was consulted in the fixing of the site of Wellington itself.

Whaler who Married A Princess.Romantic History of “Dicky” Barrett, After 85 years, Taranaki Daily News, 26 August 1922, Paperspast, National Library.

Barrett’s name remains a legacy in New Plymouth and Wellington, with Barrett Street (named by Carrington) and Barrett Road and Barrett Domain in New Plymouth, and Barrett’s Reef at the entrance to Wellington’s harbour, named in Barrett’s honour by William Wakefield. A residential sub-division near to where the Barretts and crew members were allocated land is called ‘Whaler’s Gate’.

Summary

To say that Dicky and Rāwinia Barrett led extraordinary lives is an understatement. They were both, in their own ways and as a couple, remarkable people. What stands out is that so much of their personal circumstances were interwoven with so much historical change.

Dicky’s origins were of extreme poverty where individuals and families struggled to live their lives in brutal, polluted, unhygienic ‘urban jungle’ conditions, competing for the essentials in life: protection from the elements, food and water and clothing. Add to that a long history of European and American wars and associated economic and social upheaval.

By the time he died in 1847, Dicky Barrett had been in living Aotearoa / New Zealand for 19 years. He became a ‘Pakeha Māori, living with Rāwinia’s whānua and adapting to their ways. As a ‘white chief’ he fought along his Māori kin at Moturoa and near to Wanganui.

His business interests started with being a trans-Tasman flax trader at Ngā Motu. He was head man at two onshore whaling stations. He grew vegetables and fruit and established farms, raising cattle. He acted as a guide / mentor to Māori, aiding the establishment of their own businesses trading with Europeans. He travelled widely within New Zealand and came to know its coastline very well. He became an interpreter and agent for the New Zealand Company. Dicky and Rāwinia were both influential in the NZ Company’s selection of Wellington and New Plymouth as locations for settlement. Dicky established Barrett’s Hotel in Wellington. His lived a most extraordinary life, far beyond what he could have dreamed of as a boy in East London in the early 19th century.

All of that took a huge strength of character, a man of strong mind and body. A man widely known for his hospitality and kindness to all.

Trevor Bently, in writing about the early Europeans who lived as Maori, stated that:

Pakeha Maori had significant political, economic and social importance in tribal New Zealand … Close scrutiny of the contemporary evidence reveals a unique class of men (and women) possessed of the knowledge, skills and courage necessary to live and prosper among a warrior society rent by intertribal gun warfare”.

Bentley, p 10

In contrast, Rāwinia’s origins were a place of extraordinary beauty and abundance with deep interconnections to family, community and to the land and the environment. And yet Rāwinia’s circumstances were not without brutally as evidenced by the long history of inter-tribal warfare.

Rāwinia’s life changed dramatically after she married Dicky, becoming what may be described as a ‘Māori Pakeha’. merging the customs and traditions that she was raised with to life as a wife of a European man and experiencing the early stages of European colonisation and the massive upheaval experienced by her people. Throughout their lives together, Rãwinia maintained the duties of a high-born wahine centred upon hospitality and generousity to visitors and whānau.

Rāwinia was ‘high-born’. Dicky was ‘low-born’.

While they were from vastly contrasting origins, values and cultures, they made a lasting impact particularly on the history of Ngamotu / New Plymouth and Whanganui-a-Tara / Wellington and showed that a relationship between the two cultures could be beneficial to both. Their legacy lives on.

My greatgrandmother was Susan Barrett of Sentry Hill.Any connection to Barrett/Honeyfield?

LikeLike

Hi Betty,

Not that I know of unfortunately

Regards,

Paul

LikeLike

Kia ora, There are those claiming a Richard Parete/Barrett as the father of Henare Tieke Pareti. The mother is Kararaina/Caroline Hinehou of Kai Tahu whanui,-the daughter of Mahaka and Te Hekaeko.. They connect this Richard with the same Dickie from up Nga Motu way. It is confusing, but I have an old note in my note book (unfortunately unreferenced) which indicates Kararaina Hinehou was taken prisoner from Kaiapoi pa (with her child?) up north to Kapiti Island and later returned to the Taieri, south of Dunedin. Any suggestions?

LikeLike

Kia ora Irian

I have heard of this. In her biography of Dicky (Tiki) Barrett The Interpreter, pages 149 – 150, Angela Caughey describes the account along the lines as you have indicated, but notes the “The question of whether [Henare was Barrett’s son] awaits further proof … but it seems unlikely he would have had time to stray far either from Port Nicholson or Rawinia …”

However, my genetic profile is on 23andme.com. Should one of those claiming the ancestry as you say also arranges a genetic profile with the some company, and a family relationship with me would shows up, that may well provide some evidence to support their claim.

Best regards,

Paul Roberts

LikeLike

Pingback: Ngati Te Whiti – Barrett Honeyfield Ancestry

Pingback: James and Caroline Honeyfield – Barrett Honeyfield Tupuna / Ancestry: their lives, the times and their legacy

Pingback: Te Wanau o Wakaiwa Rawinia Barrett: Nga Tupuna – Barrett Honeyfield Tupuna / Ancestry: their lives, the times and their legacy

Pingback: Establishing the trading station at Ngamotu, 1828 – Barrett Honeyfield Tupuna / Ancestry: their lives, the times and their legacy

kia Ora my name is Joseph frank barrett ,I’m looking for my gg grandfather edward barrett he is said to be son of dicky barrett n rawinia according to a arbitrary in matamata news paper .my father was arthur Edward,his father was Joseph Edward,his father was puke ki mahurangi ,his father was Edward.does anybody recognise these names .nga mihi Joseph barrett 3rd

LikeLike

Kia ora Joseph,

I’ve received a similar enquiry from another person related to Edward Barrett. Edward’s surname and that of his son strongly infer a connection to Dicky and Rāwinia and Rāwinia’s father, Te Puki Mahurangi, although there is no record of Edward being their son, or adopted son.

There is also a reference to Edward being looked after by Caroline (Kara) Barrett until they had a massive falling out when Edward was 17 and that was the end of the relationship.

There is no DNA connection between Dicky and Rāwinia’s children (Caroline and Sarah) outside of the Honeyfield whānau that I know of. It is possible that Dicky and Rāwinia informally adopted Edward but of Edward’s ancestry there is no information other than a possible connection to the Love whānau

Nga pai katoa ki a koe

LikeLike

Edward was said to have stayed with sera

LikeLike

kia Ora edward was said to have stayed with sera honyfeild and her husband until they had a falling out over i believe land .I’m looking for any info on edward as he is said to be my gg grandfather nga mihi Joseph barrett 3rd

LikeLike

Hi, I’ve stumbled across this while looking for information about my ggg grandfather, James Bosworth, I know he was one of the original crew, and that he married a Maori woman, and they had a son, who ended up in Australia, do you know anything else about him or her? I have been searching for more information about them for years, but as yet I haven’t even been able to find her name.

LikeLike

Sorry Dallas, I have not seen any information about who James Bosworth partnered with. I know that James remained a loyal part of Barrett’s crew. I wish you well in your research.

LikeLike

Thanks Paul, appreciate you replying.

LikeLike

Hey Dallas I think we are researching the same person. Are you on Ancestry.com?

LikeLike