Updated 28 January 2024

Te Puke Mahurangi and Kuramai-i-tera were Wakaiwa Rāwinia’s parents. Te Puke and Kuramai had two other daughters, Hera Waikauri and Herata Waikauri. Herata had a son, Hoera Pare Pare.

Hera married Ihaia Taiwhanga but had no issue of her own. Hera and Ihaia were given a Crown Grant of 8 acres of land ‘Moturoa F’ in 1887. Interestingly, a Maori Land Court order dated 17.7.1914 ruled, with the support of the Honeyfield’s, that the interests of Hera Waikauri in Moturoa F should go to her grandchildren Te Kauri Paraone and Kararaina Paraone (Hodgson, 2018).

Hera Waikauri and Hoera Parepare are listed as Ngāti Rāhiri tipuna (Ngāti Rāhiri Hāpu Constitution, Schedule 1).

Some time following the siege of Otaka Pā Herata Waikauri was taken by the Waikato as a slave. Following her release she did not marry and she died in Auckland in 1887.

Hoera married Mere but had no issue, but they adopted Eruera Kipa (Skipper), son of Hoera’s cousin, Neha Te Manihera. Hoera and Mere lived at the Kainga at Ratapihipihi. Hoera died in 1876 and left his interest in Ratapihipihi land to his wife and his sister, Hera (ibid). There is no evidence of Hoera and Mere having a close relationship with Rawinia’s family (i.e. the Honeyfield’s).

Little is known about Te Puke’s background. We do not know of his parents or when or where he was born although what information is available is that he is of Te Atiawa of either Ngāto Rāhiri and/or Ngati Te Whiti.

Some researchers have referred to him as a leading Ngāti Te Whiti rangatira. Evidence that he belonged to Ngāti Te Whiti is also in the results of a census organised by Donald McLean in 1847.

Te Puke was identified as one of the Ātiawa rangatira who gave some support to the Tainui/Ngāpuhi amiowhenua taua in 1819-20 when they were under siege at the Pukerangiora Pā (Smith, 2010 p362-363). That may indicate that Te Puke shared some kinship ties to the northern tribes as did Kuramai-i-tera.

Kuramai-i-tera’s whakapapa in contrast is well-established and very impressive. Through her father, Tautara, Kuramai’s whakapapa traces back to seven of the great waka that arrived in Aotearoa around 1350 (see Wakaiwa Rāwinia’s whakapapa in the family tree links page), and to several other iwi to the north and east of Taranaki. Tautara was a leading Atiawa chief (Ariki) and was known to belong to the Puketapu and Ngāti Rahiri hapū. He also lived for a time at the Rewarewa pā of the Ngāti Tawhirikura hapū.

Te Puke and Kuramai appear to have had close relationship to the area now known as Rotokere/Barrett’s Domain, probably at the nearby Ratapihipihi Kainga or Manahi Kainga. They allocated use of land in that area to Dicky Barrett for following his marriage to Rāwinia in 1828 (later known as Barrett’s Reserve C & D). Members of the Ngāmotu hapū were recorded as living at Ratapihipihi at the 1878 census of the Māori population.

Te Puke and Kuramai were part of the 300 or so who choose to remain at Ngāmotu to maintain ahi kā as opposed joining the Atiawa migration south in 1832 after the seige of Otaka Pā. Their lives from then until the return of Barrett and his family eight years later can only be described as being utter misery from subsequent raids by the Tainui. Their bravery and perseverance deserve to be remembered.

Kuramai-i-tera was also taken as a slave by the Tainui in a follow-up attack in 1833 and was not released to return to Ngāmotu until late 1839, joining her husband again at the time the Barrett’s were once more resident at Ngāmotu. Kuramai was probably in the party of former Ati Awa slaves returning from the Waikato in the company of Edward Meurant, agent of the Wellesley Missionary Society (WMS), on his way from Kawhia to purchase land for the WMS (Mullon, p11).

Conditions for those who had remained in and around Ngāmotu were very harsh. Ernst Diefenbach estimated only about 20 people remaining near Ngāmotu in November 1839, and that they ‘… lived a very agitated life, often harassed by the Waikato, and seeking refuge on one of the rocky Sugar Loaf Islands, at times dispersed in the impenetrable forest at the base of Mt Egmont, sometimes making a temporary truce with their oppressors, but always regarded as an enslaved and powerless tribe’ (B Wells, Chapter 12).

One can imagine emotions being high at the sight of Dicky Barrett, Rāwinia and family at the time of their return to Ngamotu. Dieffenbach observed that, ‘On our arrival being known, they assembled around Mr Barrett, and with tears welcomed their old friend. In a singing strain they lamented their misfortunes and the continual inroads of the Waikato. The scene was truely affecting, and the more so when we recalled that this small remnant had sacrificed everything to the love of their native place’.

Given his brave perseverance in maintaining ahi kā at Ngāmotu it is hardly surprising that Te Puke was initially opposed to selling land to the NZ Company (Caughey, 1998:134). As noted in the posting covering Barrett’s role on land sales, it was not until Barrett threatened to leave Ngāmotu once again with his family that Te Puke was coerced into signing the deed of sale.

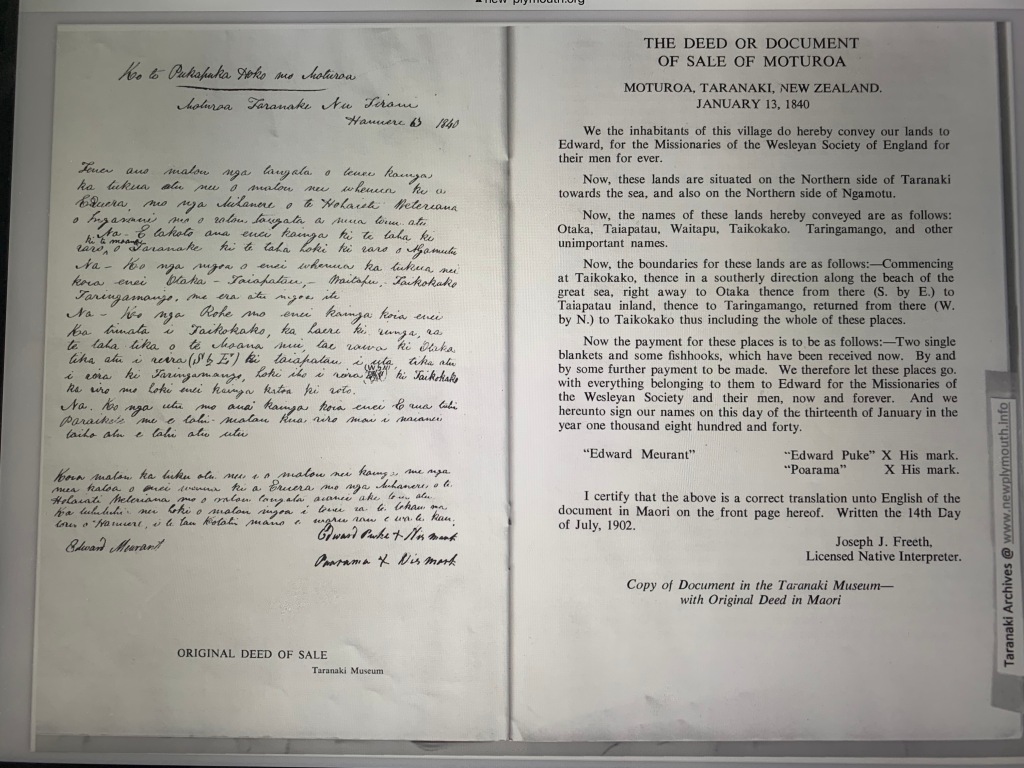

However, prior to doing so, maybe in part in response to the perceived threat from Europeans wanting to purchase land; in part due to his conversion to Christianity following the arrival of missionaries to Ngāmotu and that Kuramai had already converted while being held as a slave by the Waikato, Te Puke and another Ngāmotu hapū rangatira, Poharama, jointly signed a deed of sale of 100 acres of land to the WMS on 13 January, 1840. That was several weeks prior to Barrett transacting the ‘Ngā Motu’ sale to the New Zealand Company that included most of the Te Ātiawa rohe.

Ngamotu Deed of Sale to Wesleyan Missionary Society, January 1840

The first mission house stood at the foot of what is now Bayly Rd and what is now the Wahitapu Urupa. In time the urupa was administered by a Board of Trustees appointed by the Minister of Maori Affairs.Some of the land sold to the WMS came under Railways ownership. Later, as a result of William J Honeyfield’s efforts, a Wahitapu Trust was formed including representatives of the Love and Barrett families (Mullon, p24).

As was common practice for Māori in becoming christian, Te Puke took the European first name of Edward, or Eruera in Te Reo: hence he signed the WMS deed of sale as ‘Edward Puke’. Te Puke may have chosen ‘Edward’ in honour of Edward Meurant.

Eruera and Kuramai saw out their years living near the Hongihongi stream, close to the Barrett family at Ngāmotu. They had seen so much change following the arrival of Europeans, the consequences from the musket wars and from early colonisation. They had no doubt witnessed much joy and happiness as well as indescribable horror and hardship in their lives. For me, their great-great-great grandson, their courage, honour and dignity remain as an inspiration.

We do not know when Kuramai died. Eruera appears to have outlived Kuramai, Barrett and Rāwinia given that Poharama Te Whiti noted in his letter to Donald McLean dated 16th February 1851 that: “our elder, Eruera, who has died, and will not return as friend or guide for me and our good friend, Hone”. Both Eruera and Kuramai are likely to be buried at the Wāitapu urupa, Ngāmotu, close to the Barretts.

Kia ora Paul, thanks for your blog. We are on a similar journey. Please email if you would like to chat. fleurpurple@gmail.com, Fleur Coleman.

LikeLike